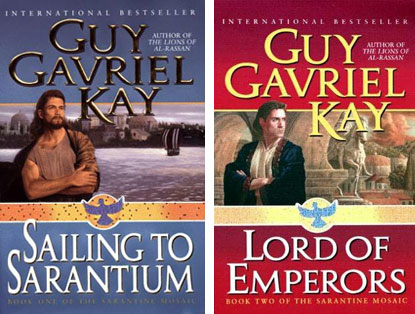

Your experience of reading Guy Gavriel Kay’s Sarantine Mosaic (Sailing to Sarantium and Lord of Emperors) is likely to be extremely different depending on how much you know about Justinian, Belisarius, and the history of sixth century Europe. There’s a way I never read these books for the first time—I was so familiar with the material Kay was using that it was like a retelling. If you’ve read more than one retelling of Homer, or of King Arthur, you know what I mean—it’s a case of interpretation, selection and shaping, rather than invention. There was never a time when I didn’t know the story to begin with, when I didn’t recognise who the characters were. And the characters are very close here—the map looks like a fuzzy Europe, and when I’m talking about the books and I haven’t just read them I’m inclined to forget Kay’s names and use their real names. Kay isn’t trying to hide the fact that Sarantium is Byzantium, Varena is Ravenna, Valerius is Justinian, Pertennius is Procopius, and Gisel is Amalasuntha. If you don’t know who those people are, your reading experience would be a discovery. If you do, then it contains a lot of recognition of how clever Kay is being. Yet Kay clearly expects a certain amount of real world context to intensify and contextualise the story he’s telling. You can enjoy the story without ever having heard of Amalasuntha or iconoclasm, but you’re expected to recognise Asher as Mohammed and appreciate the implications.

The question this demands is, if he’s going to keep it that close, why not write a historical novel? Well, the advantage of re-writing history as fantasy is that you can change the end. You don’t even have to change the end in order to get this advantage. Because it’s fantasy, because you have changed the names and reshuffled the deck, nobody knows what’s going to happen, no matter how familiar with the period they are. I realised this half way through The Lions of Al-Rassan with a shock of delight. Kay talks about respecting the historical characters by not writing about them directly, and the ability to make things clearer by purifying and condensing events and issues, and that’s also an advantage, but a historical novel is inevitably a tragedy, a historical fantasy is open.

I’ve worked out why everyone is so interested in Justinian and Belisarius. It’s because of Procopius, Justinian’s official historian. In addition to Procopius’s official history, in which he is deferential to hagiographic about the characters, he also wrote a secret history in which he vilifies them. The contrast is clearly irresistible. (Kay also couldn’t resist having Crispin punch Procopius/Pertennius in the nose, and I have to say I couldn’t have resisted it either.)

These are weird books. They’re written in an odd, distanced, elegaic style that I want to call veiled omniscient. The omniscient narrator knows what will happen, and what did happen, and what everyone thinks, but doesn’t like to approach too closely. He draws and lifts veils. He plays tricks where he described but doesn’t say who is who—does anybody like this? I hate it when Dorothy Dunnett does it, and I hate it here, too. If a blonde woman comes into the room, don’t leave me guessing who it is for two pages, this will not enhance my reading experience but rather the opposite. There’s a sense here that we’re always looking through the wrong end of the telescope, that these people are far away. Sometimes this makes for very beautiful writing, but there’s always a pulling back. There’s blood and sex and love and death, but they’re interpreted through the consciousness of artifice. It’s amazing that Kay makes this work at all, and it mostly does work. There are many points of view, but he never takes up a character just to throw them away. The ironic linking of everything together in omniscient connects and underlines and is sometimes incredibly beautiful.

What Kay does supremely well here is evoking the world, juggling the city and the empire, the neighbours, the gods, competing religions and heresies, chariot racing, factions, mosaics. The details are all real enough to bite, the varying quality of the glass tesserae, the mud, the fish sauces, the tool for drawing out arrows from flesh. The details are right for sixth century Byzantium, and even where he’s made them up they feel right.

Kay mediates the world through the chariot races and the making of mosaics, he often describes it in those terms. We get the heresy and the religion through the mosaics. We get life and control of the empire through the chariot racing—sometimes as a metaphor and sometimes for real. There’s a set piece race in each book, both different, both splendid. The pacing of events is unusual, it tends to concentrate on single days in which many things happen, with lots of flashbacks and remembering—there’s more use of the pluperfect tense in these than anything else I can think of. This single day thing is almost like Ulysses—there are a lot of characters, a lot of events, all compressed into a small moment of time. You’ll have a chariot race and see it from the point of view of a driver, someone in the crowd, an undercook for the Blue faction making soup.

The main character is Crispin the mosaicist. After a prologue set in Sarantium at the time of the accession of Valerius I, the arc of the book follows Crispin’s journey from Varena to Sarantium and back. We spend more time with Crispin than anyone else, and Crispin is more deeply embroiled in events than quite makes sense. This is fairly normal in stories with a protagonist, but odd in something so relentlessly omniscient. Crispin is so passionate about his mosaics that you can almost see them. And through the course of the books he makes an emotional journal come back from not caring about life.

There’s more magic than there was in The Lions of Al-Rassan, but not much for a fantasy novel. There’s an alchemist who embodies human souls in birds, and there’s a truly numinous encounter with a god. That’s amazing. Beyond that there are a few inexplicable flashes of flame in the streets and some true prophetic dreams. It’s not much magic, but it runs glinting through everything else like the silver threads in shot silk.

This is an incredible achievement, and it may be Kay’s greatest work.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published eight novels, most recently Half a Crown and Lifelode, and two poetry collections. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.